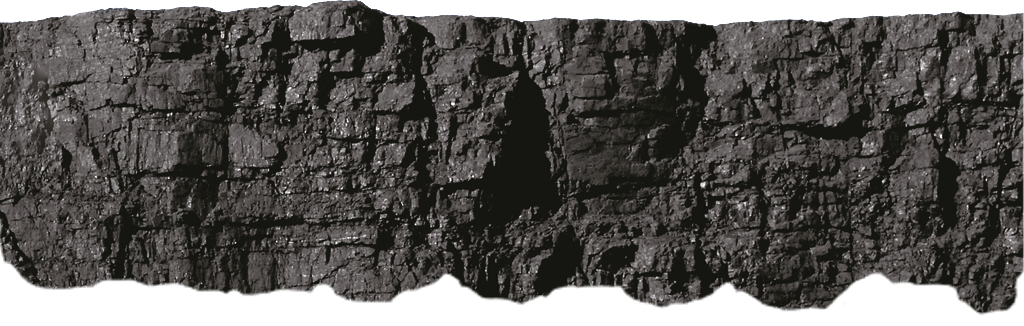

When they arrive in Schalke, the new arrivals doubt whether they are still in the year 1895. The Consol colliery lies before them, stamping and snorting like a huge monster. Wheels turn incessantly, pit cages rise and fall. Railways drag endless rows of coal wagons behind them. And above them, the chimneys hurl smoke and flames into the sky. Nothing here was like back home. But that's why they were here: There was work here and a way out of poverty, and that leads down into the depths of the mountain. No previous experience is necessary. They learn on the shift, before the coal. And when there's enough money, we'll have our own little house with a garden. But could it all really be as nice and easy as the recruiters had made it out to be in the pub back home?

Now they have to find their accommodation, their new home. The dirt roads are full of people. They have never seen crowds like this before. There is little space between the two, three and four-storey houses. Schalke is cramped. Also because living space is a scarce commodity. Too many people flocking to the Emscher in too short a time. The cities and authorities are overwhelmed by the developments. And they are too cash-strapped to build flats and houses for the people. In Schalke, the Consolidation colliery steps in and builds apartment blocks and housing estates around its facilities. Wherever there is still a shred of space, two, three and four-storey houses are built around the plants, equipped with the bare necessities. A washbasin in the corridor, outhouse toilets in the courtyard. The flats are rarely more than 60 square metres in size. Six or more people live in them.

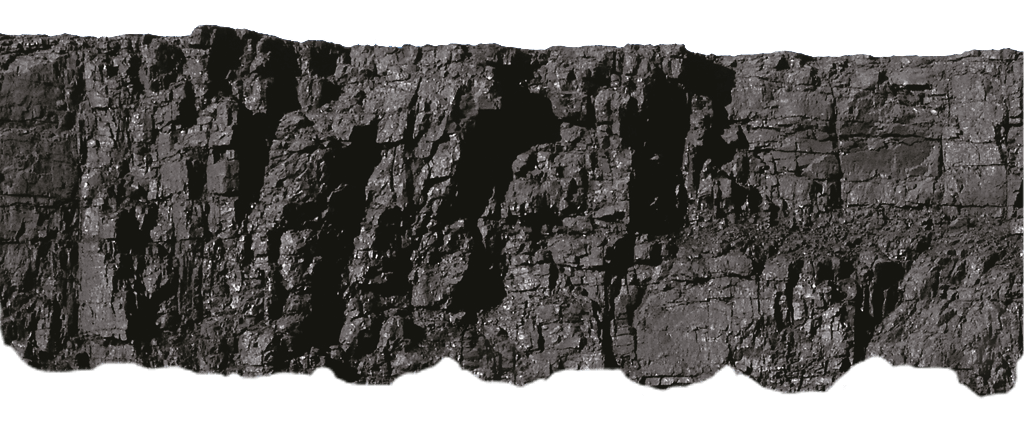

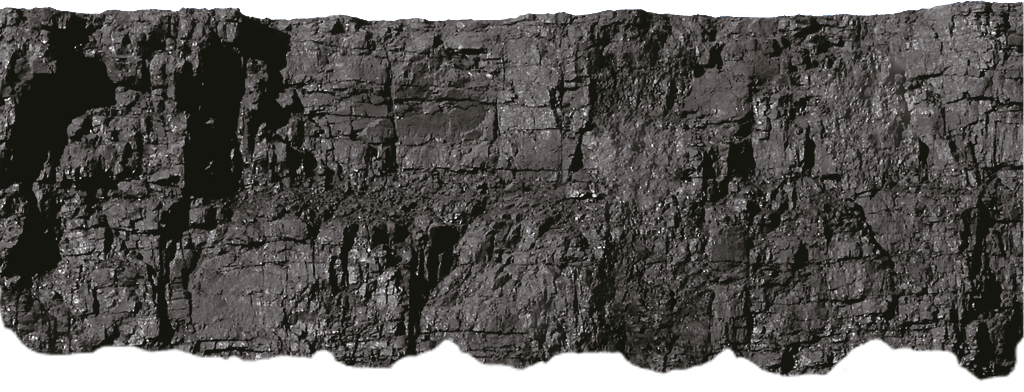

They have finally found a place to sleep. They are exhausted and tired after the long journey and the new impressions. Some of them have found accommodation with relatives. They have been here for a while and they know what it's like "underground". What can the newcomers expect on their first day? In the flickering light of a candle, they hear how the pit cage will take them down to their level - their floor in the mine. From there, they walk along the track with its rails, and then it's up into the longwall face. The longwall face is their destination, and this is where they hew the coal for the duration of the shift - eight hours. At the end, they walk back along the track to the pit cage. But they have to be there on time. Because if you miss the ropeway, you have to wait for the next one. And that can take three quarters of an hour.

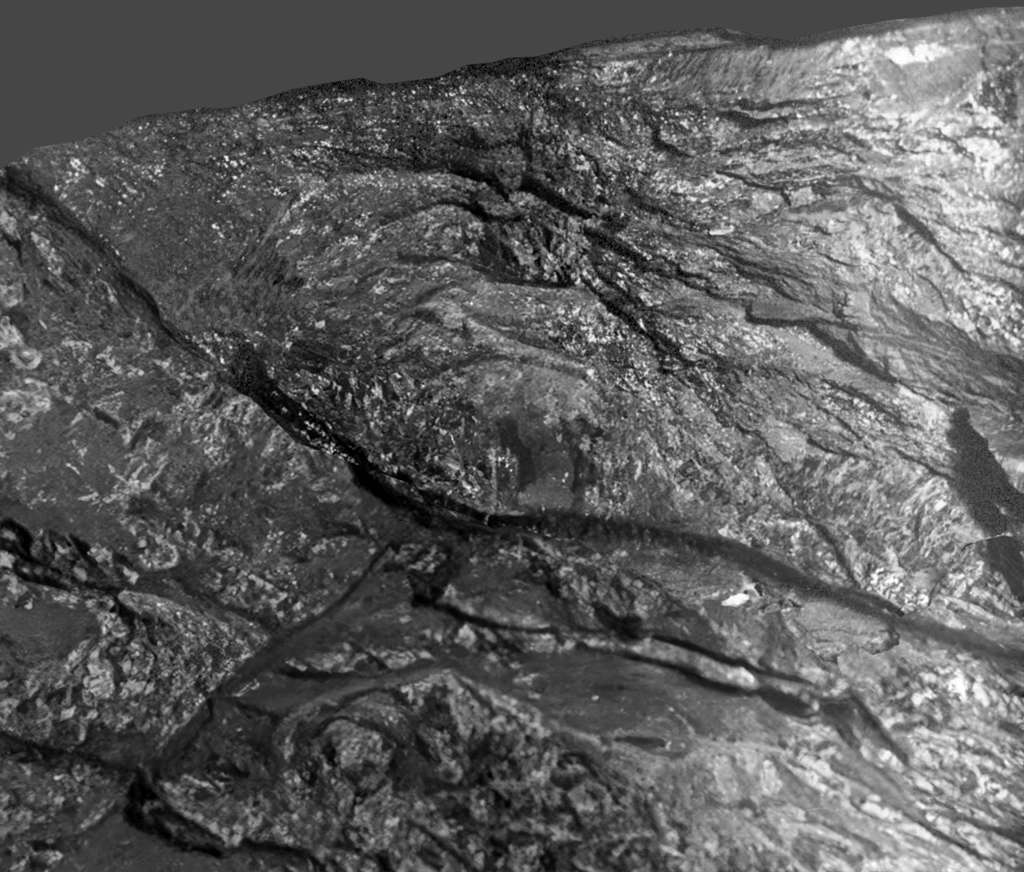

The next morning, they stand in a long queue. In front of them, two pit cages rumble incessantly down into the darkness. Then it's their turn. After a journey lasting several minutes, the lift spits them out again. Down here it is dark and stuffy and humid, almost 30 degrees. Like the others, they take off their shirts and jackets. Some people's hearts race as they realise that a layer of earth and rock almost a kilometre thick lies above them. Their breaths become short and heavy. But there's not much the lungs can do to clear the stuffy haze. When they reach daylight again after a seemingly endless layer, some of them get out of the pit cage with trembling knees. The next day, a few of the new faces are missing from the queue.

After their shift, they talk to their new colleagues. They tell them about the dangers underground. How the miners are crushed when the longwall suddenly breaks and rock and stone rain down on them. How water can break in and take everything with it through the tunnels and into the depths. Of explosions that race through the corridors in flames when gases are ignited somewhere. And even if everything goes well, the wire rope of the pit cage can still break on the way back up. But the greatest fear of all miners is being buried alive. To whisper prayers into the rock alone deep in the darkness and ask to be rescued. Just like ten years ago, when parts of the morning shift at Consol were buried in an explosion. 56 miners died on 24 September 1886 and they too will have whispered a final prayer into the mountain.

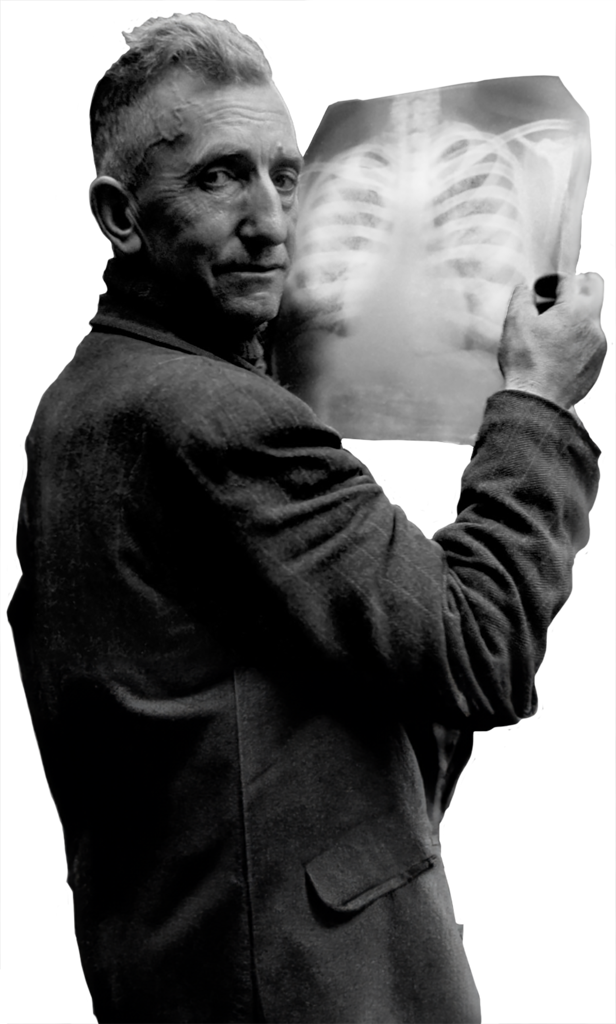

The major mining disasters bring more and more disasters in their wake. Families who lose their fathers are suddenly left to fend for themselves. But the hard labour and working conditions also take their toll: by their mid-40s, most of the miners are exhausted and at the end of their tether. They can no longer drive in. Those who are unlucky can only spend their last years - if at all - gasping for breath on their beds. The work destroys their lungs. The smallest rock particles settle in them without them realising it. Only much later, when too much of the lung has been scarred by the particles, can they hardly breathe. In severe cases, they even suffocate from the disease.

In this dangerous world, they look for things that give them stability. For one thing, there is the camaraderie underground. Everyone helps everyone here. The other is religion and piety, both of which are very important to them. In view of the threat of disaster underground at any time, a close connection to God is even more important. The miners - no matter where they come from - seek support as often as they can in the Friedenskirche church on Schalker Markt and St Joseph's Church on Kaiserstraße. They never miss a service. The fear of sudden death unites them across all denominations. There is even a patron saint for the miners: St Barbara. She protects all those who are threatened by sudden and sudden death. But nobody in the Ruhr area knew her yet. This only changed after the Second World War.

After the end of the Second World War, new people arrive again. Displaced people from Upper Silesia hope to find work among the ruins of Schalke. But not only Schalke, the whole country lies in ruins. To rebuild it, men are once again being sought for the mining industry. Housing is scarce. Only single men are recruited to support the remaining miners from Schalke and Gelsenkirchen. Like the Masurians, they also come to Schalke to seek their fortune. The Silesian miners bring small figurines or pictures of Barbara in their suitcases. The new arrivals from Upper Silesia celebrate their customs. The 4th December of each year is dedicated to Barbara. And her support is still needed. Even though safety precautions and the training of miners have improved: The profession of miner remains dangerous.

800,000 new miners are hired in the first decade after the war, as the Ruhr mining industry is the engine of reconstruction. Politicians support the integration of the "newcomers" with various initiatives. Religion is an important focal point. The old residents quickly adopt the traditions introduced by their neighbours. They celebrate St Barbara's Day together on 4 December, or sit next to each other in the pews at Sunday mass. It also quickly becomes an integral part of Schalke's history.

Soon more workers are needed as the economic upturn leads to a shortage of labour. This time, the recruiters are looking for young men in the Mediterranean region to bring them to Germany for two years as guest workers. The Ruhr region becomes a focal point. With the people from Morocco, Tunisia and Turkey, a new religion also finds its place in Schalke: Islam comes to Germany. However, there is not much contact between the "guest workers" and the Germans. Language barriers, religious differences, but also the belief of the locals that the young men will be gone again in two years, prevent this. Even if living together above ground is characterised by obstacles: underground, everyone can rely on each other, no matter where they come from, no matter which God they pray to.

And they will probably all be praying. Because working in the mine is still dangerous. On 16 February 1984, a longwall face breaks at Consol. The falling rocks trap ten men at a depth of 1,050 metres. Rescue workers were only able to bring five of them back to the surface dead. Four of them are from Turkey, the fifth victim is German. Even in mourning, the differences cannot be overcome. While there used to be a joint funeral service for Catholic and Protestant victims, the religious dividing lines could not be overcome this time. FC Schalke is not impressed by this: Consol is its colliery, and anyone who goes to Consol is part of the Schalke family. The miners raise money for the bereaved of the miners with a charity match. Ernst Kuzorra is also at the stadium on this day to honour the memory of the five deceased. He knows the world underground, he knows the time when Masurians and Germans were not yet on friendly terms. And he was there when the rifts slowly closed through the club. And he is certain that it will be the same this time. It just takes time.

Image sources: Fotoarchiv Ruhr Museum, Institut für Stadtgeschichte Gelsenkirchen, Montanhistorisches Dokumentationszentrum (montan.dok) beim Deutschen Bergbau-Museum Bochum