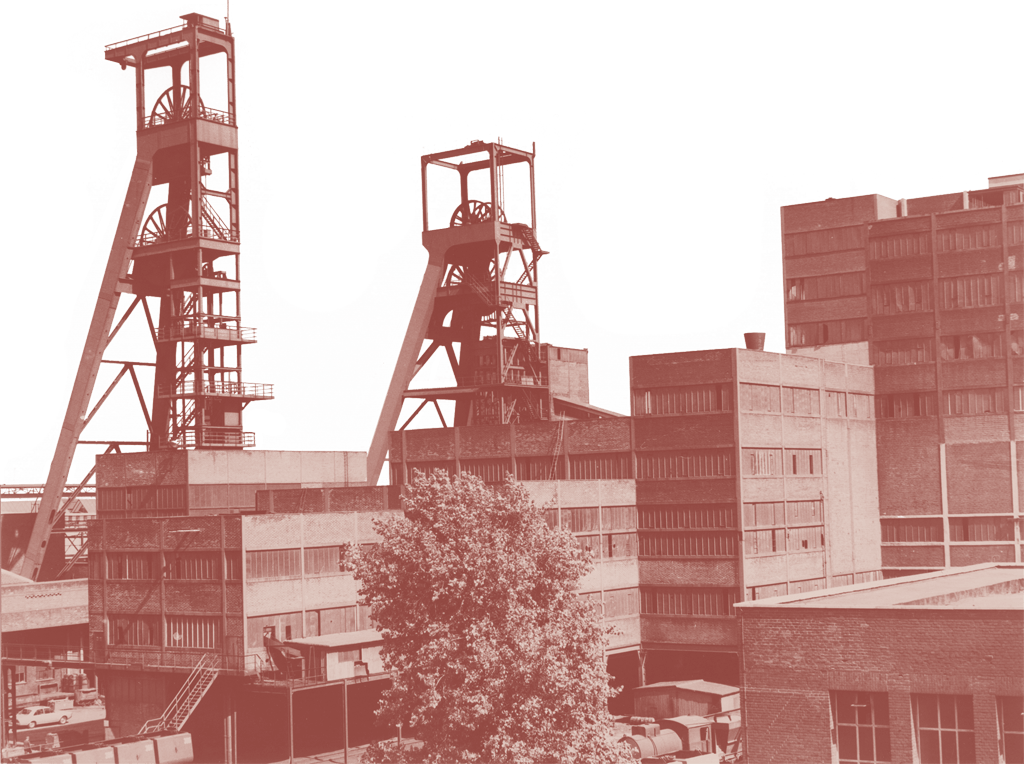

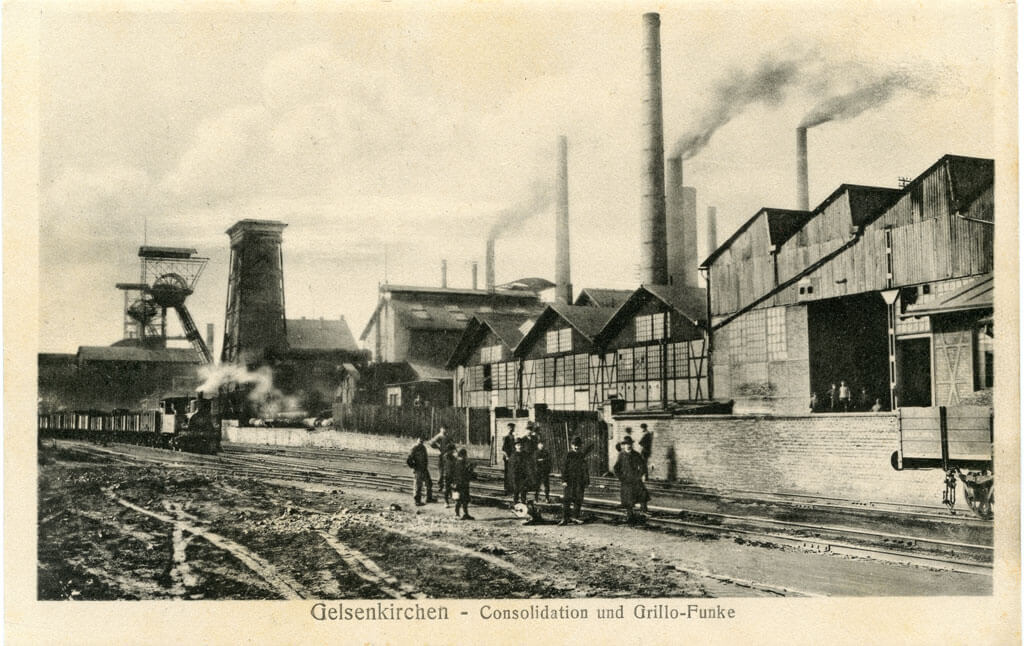

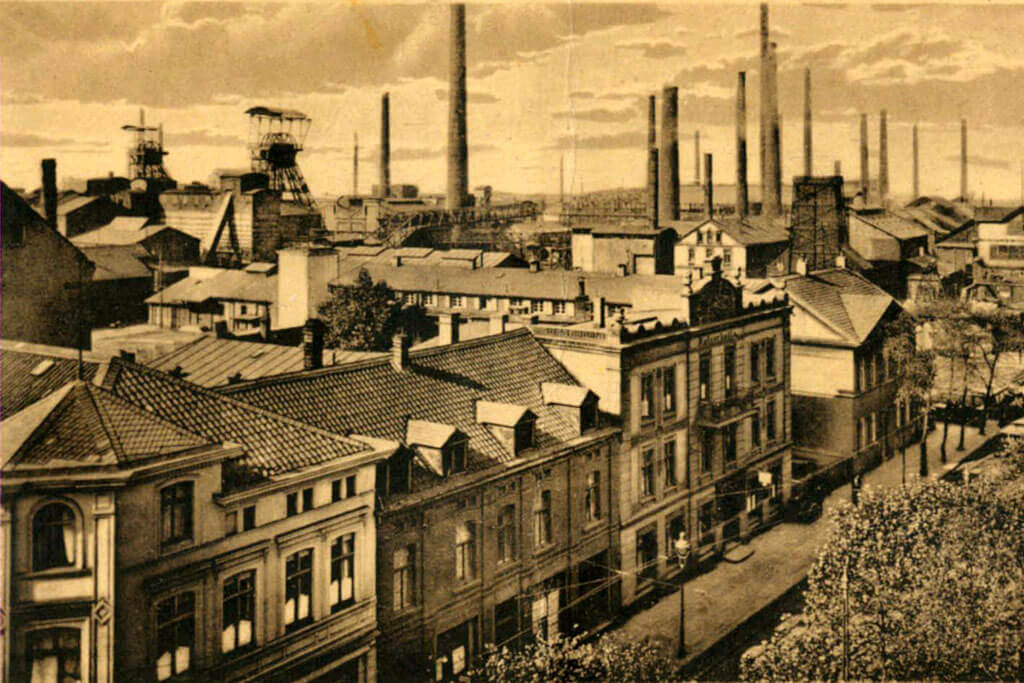

Karl is a miner. He and his wife Bertha have lived in Schalke since 1890. In their homeland of Masuria - an eastern province of the German Reich - the recruiters promised good wages and their own house with a stable. Karl signed on at the Consolidation colliery. He had never seen the inside of a mine before. The work is hard, physically demanding and not without danger. But the pay is good and the money is enough for a small four-room flat on the third floor of a block of flats. They live here with their three children. There is only one washbasin on the floor for several families and an outhouse for all the residents in the courtyard. There is no bathroom. That is more comfort than they could ever have dreamed of in their old home. Nevertheless, life here is full of privation. To make ends meet, Karl and Bertha keep two pigs and grow vegetables. On 16 October 1905, a cloudy Monday, their fourth child is born. They name it Ernst...

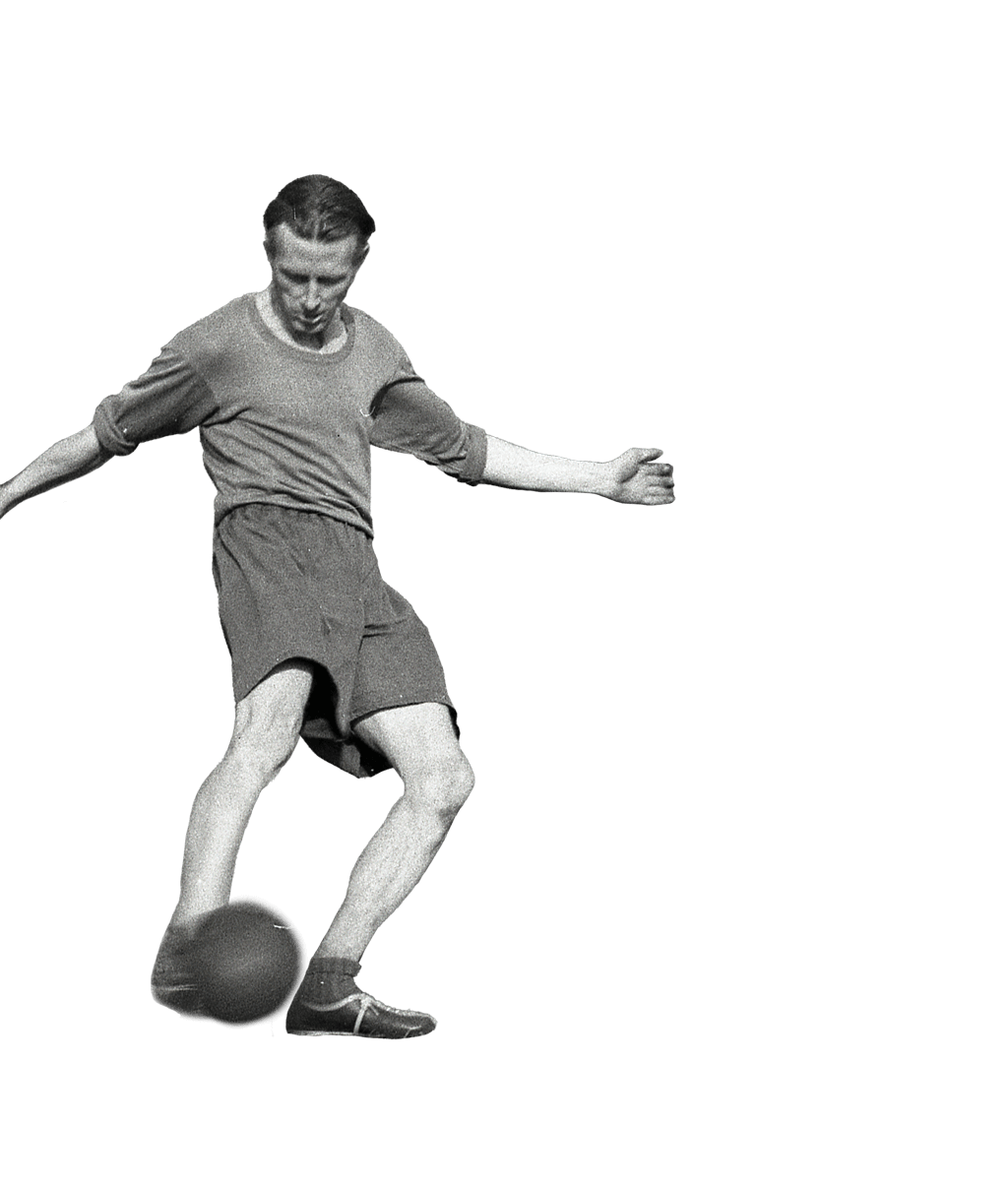

Even at a young age, Ernst kicks anything that comes his way: stones, cans, it doesn't matter. But the best feeling is when he meets up with the other boys. On a bumpy meadow next to the Church of the Redeemer, just a few metres from Ernst's parents' house, they play as much and as often as possible. They have made their own ball out of rags. They can't afford a real football. Football boots even less. They play in their good leather shoes. When Ernst comes home after playing, there's not always just trouble - sometimes there are blows when Karl and Bertha see the ruined shoes. The parents don't like their son's passion at all. He only dreams of one day playing for SC Gelsenkirchen 07 alongside the "fumble king" Michael Gogalla. But things turn out differently. The day after his confirmation, Ernst strolls off in 1920 to watch a match between the B-youth team of Erle 08, one of the best youth teams in the area. Their opponent is Schalke 77...

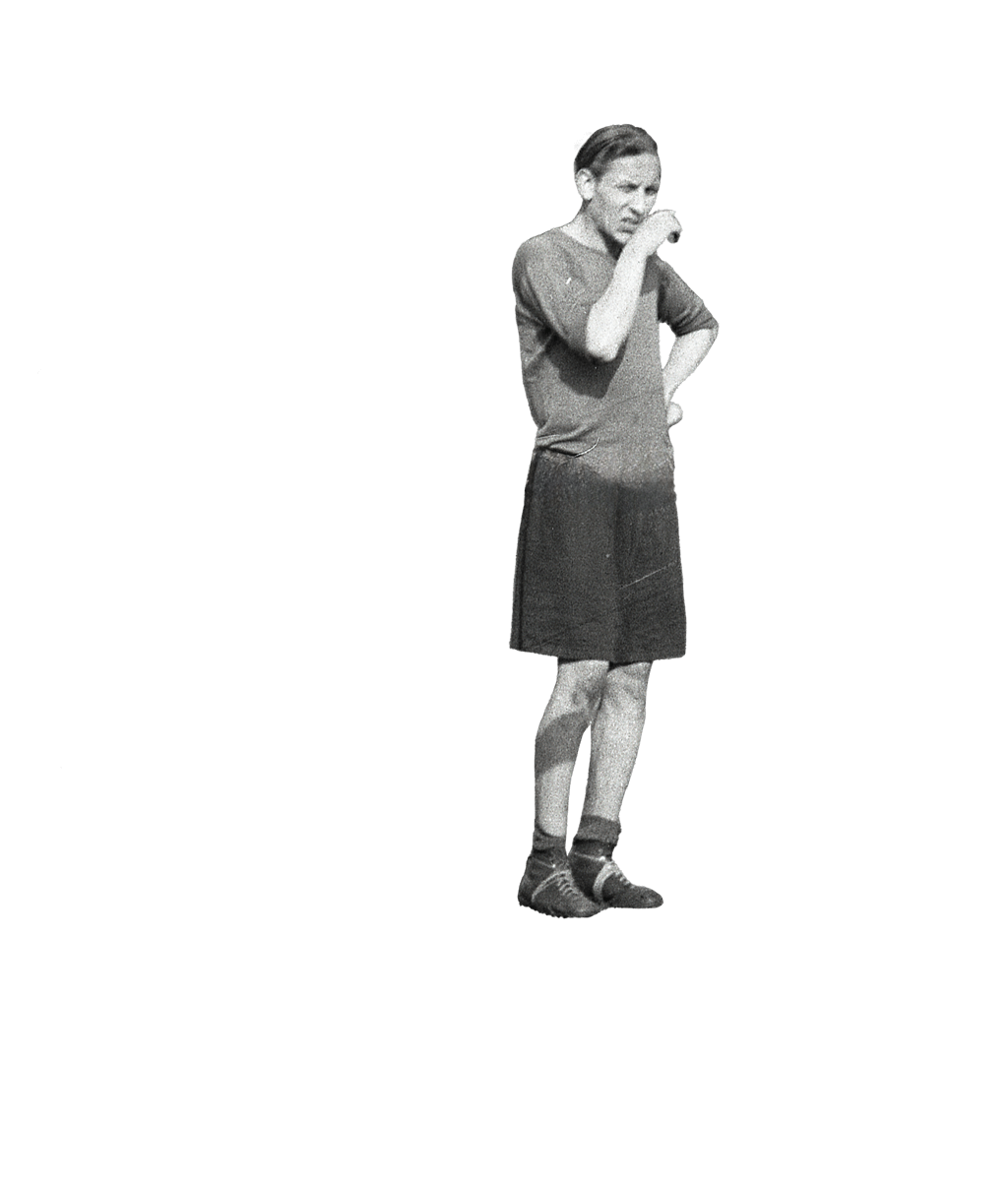

Schalke are missing one player. One of them is a classmate of Ernst's. When he recognises the talented dribbler among the spectators, he runs to the coach and shouts: "Take that little guy, he can do something!" And how he can do something: In his first match, the young Ernst scored two goals to give Schalke victory - in his confirmation shoes. Like his great idol Michael Gogalla, he dribbles his way through the opposing ranks. When he gets home, he hides his shoes in the stable. When his parents find out the truth, they ban him from playing football. But Ernst is unstoppable. His world now only revolves around football. He sneaks off to training and spends every spare minute with the Schalke players. But the free minutes have become fewer. At the age of 15, he starts working at the Consolidation colliery. First above ground on the conveyor belt, two years later he began an apprenticeship as a hewer at Consol. From then on, it was down into the depths. The shift down in the mine began at four in the morning. The work is hard, it saps your strength.

But Ernst is lucky: his work colleagues know what outstanding skills he has in the field. To ensure that their "Clemens" - as they called Ernst - was fit for the games, they gave him easy tasks on shift. While Ernst improves his technique and game in the youth teams, two new players join the first team. Brothers Fred and Hans Ballmann return to the Ruhr region in their mid-20s after spending almost their entire lives in England. From the motherland of football, they bring with them a system of play that nobody in Germany knows: the Scottish short passing game. In this country, teams simply bolt the ball forward wildly in search of a quick finish. The Ballmann brothers, on the other hand, instil the combination game in the Schalke players. They let the ball run and play their opponents dizzy. In 1923, Ernst moves from the youth team to the first team. He quickly internalises the system. Thanks to his skills, he soon became one of the leading players in the team.

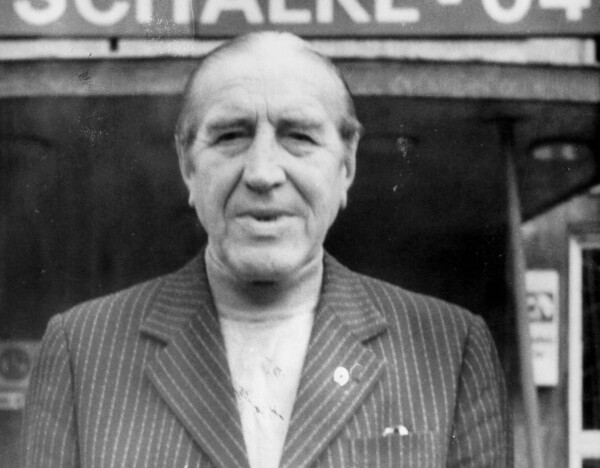

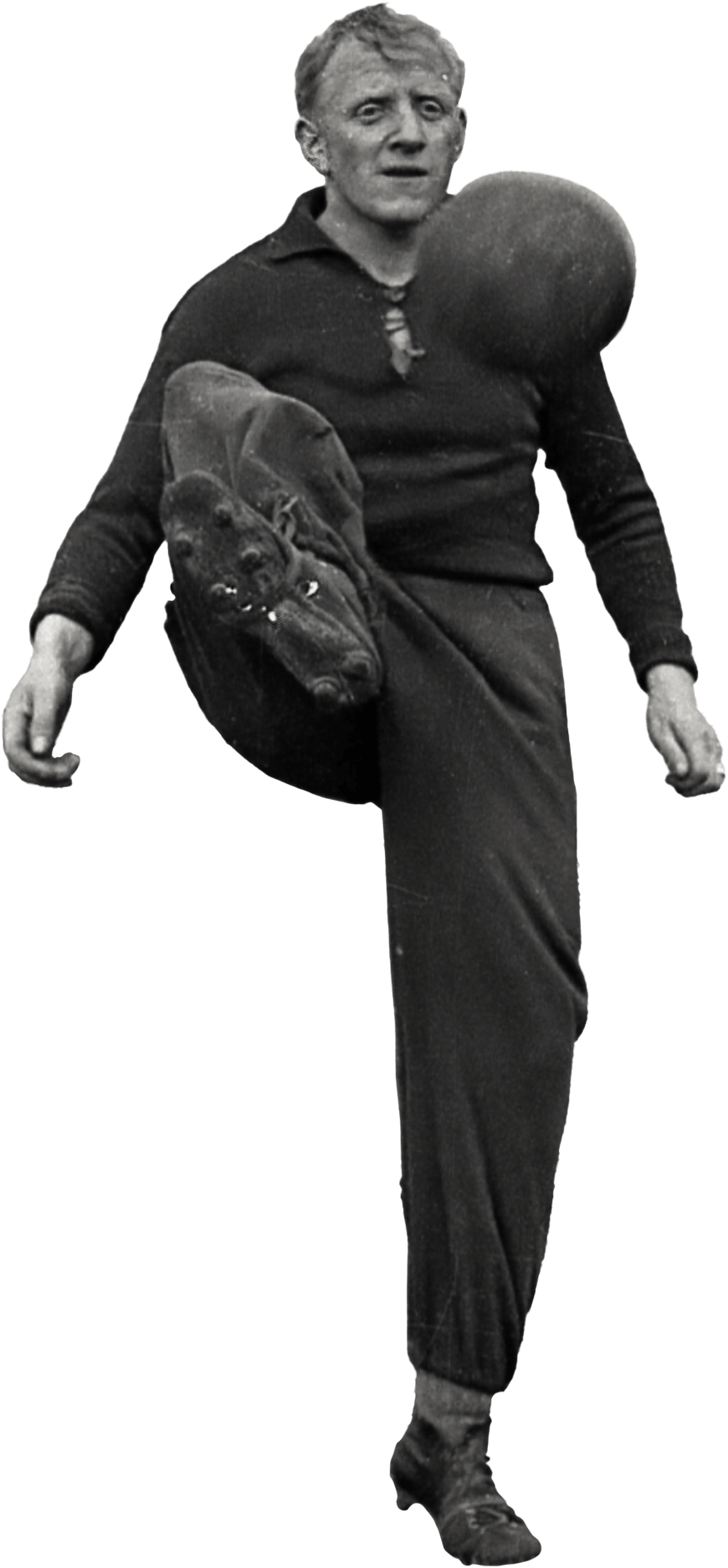

In 1925, Ernst brought 18-year-old Fritz Szepan - later to become his brother-in-law - up from the youth ranks. The other players are not keen on the idea: Fritz is not fast enough, they say. He's not a strong dribbler either. But Ernst has seen how Fritz can undermine entire defences with just one pass. He is the perfect counterpart to Ernst Kuzorra's dribbling strength. The two best pupils of the Ballmanns lead Schalke to their first successes. In 1926, they were promoted to the Ruhrbezirksklasse, the highest division of the West German Football Association. In 1927, they celebrate the district championship at Schalker Markt. They then compete for the West German championship against the champions of the other three district divisions from Cologne, Düsseldorf and Bielefeld. They finish second. Schalke is a household name beyond the borders of Gelsenkirchen and the Ruhr region. The team is a new force in West German football. The people of Schalke are proud of their boys. In 1929, they win the West German championship. The Schalke market trembles...

More and more people from all over the Ruhr area want to see the Schalke roundabout. As early as 1928, the club inaugurates its new stadium, the Glückauf stadium, which has 34,000 seats. The fine technicians and the teamwork of the miners inspire people. Even a one-year ban on the "Arbeiter- und Polackenverein" didn't change anything: 70,000 people overran the Glückauf stadium at the first match after the ban to see their Schalke team. And they are unstoppable. In 1934, Ernst and the others reached their peak for the time being. They made it to the final of the German Championship. It is the national Champions League, only the best German clubs play in it. On 24 June, they face five-time champions 1. FC Nürnberg in Berlin. Of the 45,000 spectators, 3,000 Schalke fans have travelled from the Ruhr region, some allegedly by bike. Perhaps the first of them regretted it when Nuremberg took the lead with a goal in the 54th minute. Ernst drives his team on in the humid Berlin air. The miners pinned Nuremberg back in their own half, but the equaliser would not come. The opponents threw themselves into every shot. Shortly before the end, Ernst's strength is almost gone. His groin has been hurting for weeks. But then Fritz scores to make it 1:1 - the supporters wake up. 87th minute, there's still time. They push their team forwards with shouts of "Schalke". Ernst pulls out the last reserves. In the 90th, the ball lands in his hands. He doesn't know how, but it doesn't matter. He takes a shot. The ball bounces into the net. Schalke are German champions for the first time.

The news spreads like wildfire on the Schalke market. Rumours mingle among them. One person claims to have heard that Kuzorra collapsed unconscious after his winning goal. The pain from his hernia had become too much. When the squires arrive at Gelsenkirchen central station with the Victoria statue - the championship trophy - they are confronted by a sea of people. The whole city is there to greet their heroes. The players are driven through Schalker Straße to Schalker Markt in horse-drawn carriages. There they present their trophy to the cheering crowd. Ernst Kuzorra is 28 years old. He looks into the faces of his neighbours, friends, former colleagues and family members. He sees their eyes light up, some of them glistening with tears. Ernst knows that the trophy means just as much to them as it does to the players. And he can see how proud they are that a few of their boys have led the club to the very top of German football. But this is just the beginning: the Schalke top will dominate German football for the next eight years. For the next eleven years, the West German champions will be Schalke 04, who will win the German championship five more times and the cup once. The myth of the Schalke market is born.

The miners have been playing their way into people's hearts since the end of the 1920s and in the 1930s. The National Socialists tried to capitalise on this popularity. A successful "workers' club" fits too well into the narrative of the National Socialist Workers' Party (NSDAP). The Schalke players never distanced themselves from the inhuman ideology and the criminal system. FC Schalke 04 cannot escape the political and social climate. Soon after the National Socialists came to power, the club began to exclude Jewish members. Among them was the club's second chairman: Dr Paul Eichengrün had to resign from office in 1933. Some players and officials joined the NSDAP. Nevertheless, none of the members were fanatical and active members of the NSDAP. Nor did they criticise the regime or oppose its policies.

When the war is over, Schalke lies in ruins. The Kaiserhallen, the clubhouse on Schalke's market square, has been reduced to rubble. Ernst lends a hand, clears away the rubble and dirt and sets up his third tobacco shop in Schalke. He can also be seen with a pickaxe in his hand during the reconstruction of the Glückauf stadium. He helps out in the team together with Fritz. Although both were already over 40 years old. Because of the war, the Schalker Kreisel fell apart. Because of the war, there are no youngsters to replace the champion team. Ernst and Fritz directed their team-mates as they had done in the past. But the many battles they fought together have left their mark. They can no longer do what they used to do. In 1950, they bid farewell to their audience. In their farewell match, they played against a Brazilian team. They enter the Glückauf stadium in royal blue for the last time. After 20 minutes, the referee interrupts the game. Ernst looks for his brother-in-law. The two embrace. The 30,000 people in the stadium applaud their idols. With bouquets of flowers, the old Schalke disappears into the darkness of the catacombs.

Image sources: FC Schalke 04, Institute for City History Gelsenkirchen, Karlheinz Weichelt Collection