The history of the Ruhr region is a grin. The teeth gleam white in a face blackened by coal and dirt. This is how the men come out of the pit after their shift. They haul up the coal. Every day they fight against the forces and dangers of the mountain. This is how they characterise the Ruhr area and make the region what it is. They look after their families with their own hands and put food on the table. And on Sundays they are at the football match, either as spectators or players. What has little place in this narrative of the Ruhr are the women.

Their part in getting the children through is at least as big. But they have to find their own ways to do this. On the one hand, it scratches men's sense of honour when their wives go out to work.The neighbours must then think that as a man they are not able to support their family. But there are also various reasons why people at the collieries are against working underground.

But often the income from mining is not enough. There are not many job opportunities for the women. Those who are lucky can "take up a position" and help out in the household of a middle-class family. But the number of doctors, teachers and colliery directors is also limited. So earning money is by no means always an option. But work is not only a source of income, it can also save money. The men's wages are often not enough to put food on the table. The women grow vegetables behind the house or on a free piece of land. And they keep animals. At home, they mend every pair of trousers, a thousand times if necessary. The main thing is that they last a few more months, maybe years. They often rent out the family beds during the day to boarders: single young men who can't afford their own flat. The miners' wives cook for them and wash their clothes, while the young men lie in bed and sleep during the day. At night, they went down into the mine. This is how the women looked after their families until 1945.

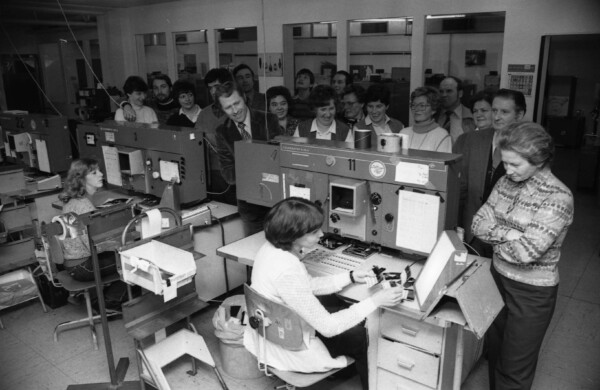

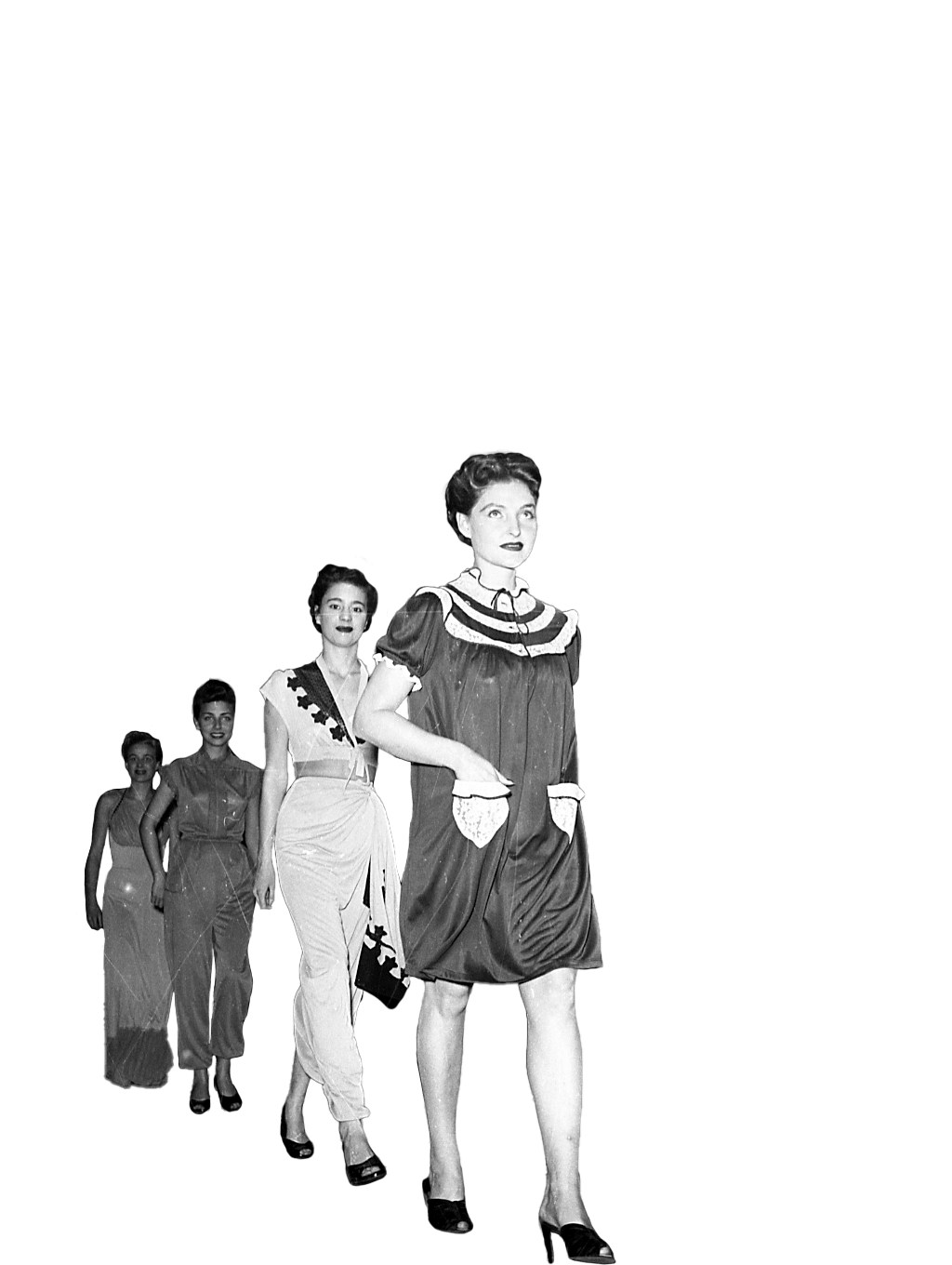

After the Second World War, a new industry comes to the Ruhr region. Many textile companies and entrepreneurs flee from the eastern regions of the German Reich. The politicians in Gelsenkirchen sensed an opportunity. They make a real effort to attract the textile industry. They provide the entrepreneurs with favourable premises or help them find suitable land. Thanks to the "Gelsenkirchen way", the city developed into a stronghold of the German clothing industry in the 1950s and 1960s. The industry brought more than just mannequins and fashion designers to the city. In the factories, women suddenly had countless opportunities to find work as seamstresses or ironers. In 1950, around 5,000 people were working in the 50 factories, the majority of them women. Daughters in particular start working to support their families financially until they start their own.

The "Gelsenkirchen system" works: The arrival of the East German textile industry adds another pillar to the city's economy: alongside coal, steel, chemicals and glass, it now also includes clothing. The city develops into a small Paris on the Emscher. Not a month goes by without a fashion show. The models present their new looks on the catwalk. While they present the clothes with their backs straight, the others bend over the sewing machines on old, uncomfortable chairs a few metres away in the narrow, dark and stuffy factories. Eight hours a day, six days a week. When the women leave the garment industry, they suffer from damaged discs or cervical spine syndrome. The decline of the Gelsenkirchen textile industry begins in the early 1970s. The competition from cheap products from all over the world is too great. A total of 7,400 people, most of them women, fear for their jobs in Gelsenkirchen.

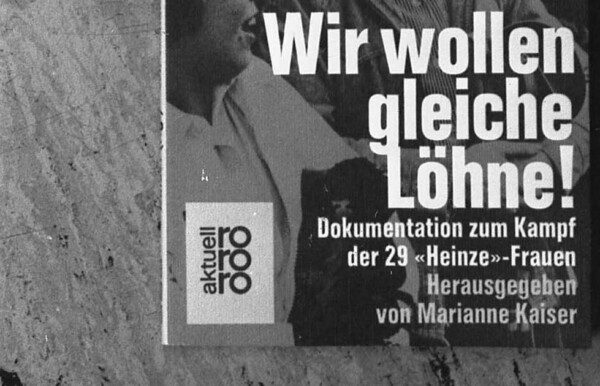

The threat of factory closure becomes a constant background noise for the seamstresses. The clothing companies often use the plant closure as a means of exerting pressure. As a counter-reaction, more and more women are getting involved in the works councils. But they cannot stop the developments: in the end, the vast majority lose their jobs in the textile industry. But women in Gelsenkirchen, such as the Heinze women, also lead successful labour disputes. By chance, they discover that their male colleagues in the Heinze photo lab earn more - for the same work. 29 of the employed women go to the labour court and demand equal pay. Their fight for equality is supported by a wave of nationwide solidarity. In 1981, the court rules in their favour and awards them 100,000 marks in back pay. However, the Heinze company has to file for bankruptcy in 1983. The 100,000 marks are only paid out in part. Nevertheless, the Heinze women's victory is groundbreaking for equal rights.

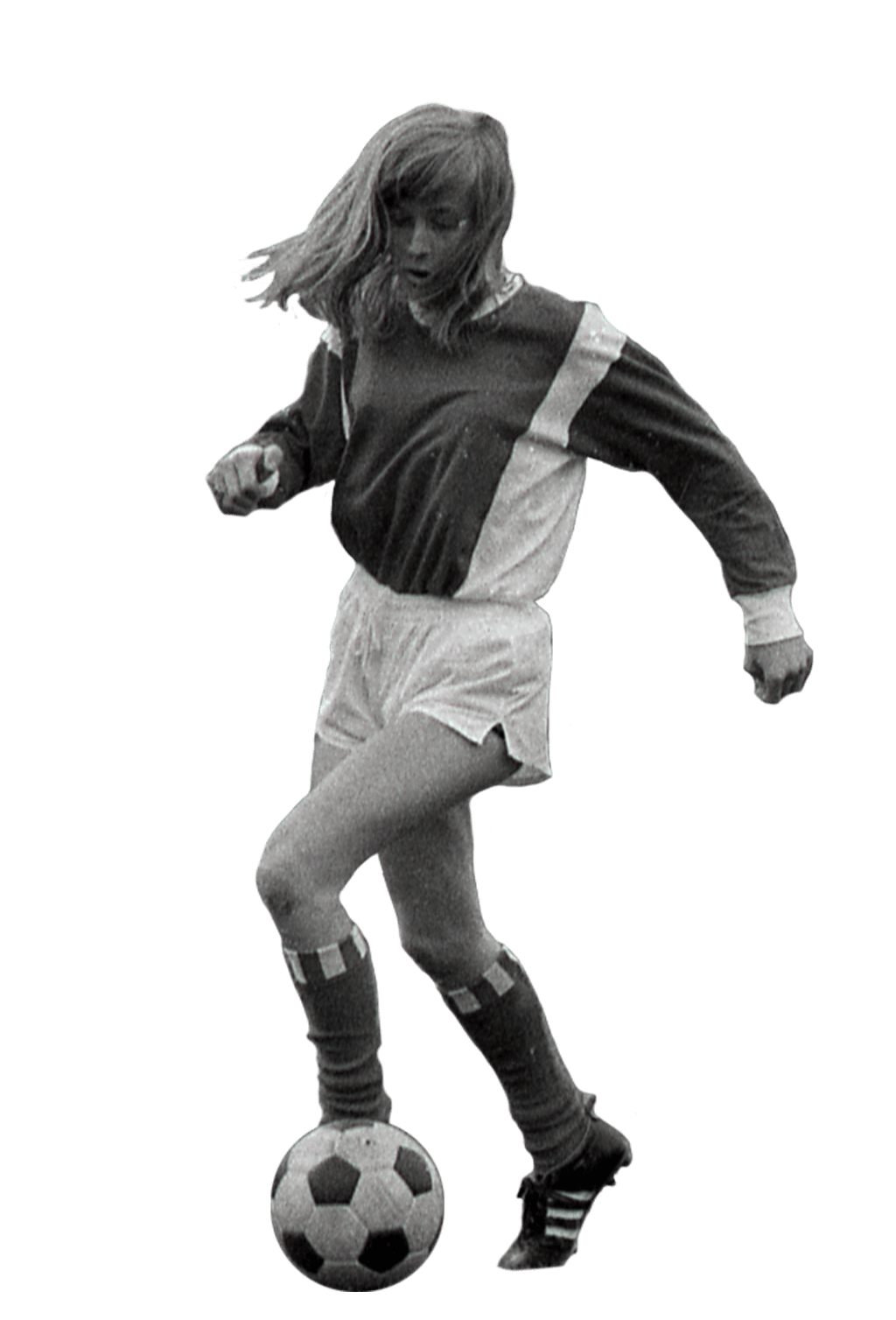

Since the Second World War, women have also been fighting for equal rights on another field: the football pitch. Because a powerful opponent is standing in their way. The German Football Association (DFB) wants to prevent women from playing football at all costs. The damage to female grace and morality was too great. A ban is issued in 1955: Women's clubs were not permitted. However, some women are not impressed by this. They nevertheless founded their own clubs outside the association and organised their own games. It took a few years, but then the DFB realised that it could not stop women from playing. In 1970, it lifted the ban. Nevertheless, the DFB introduced different rules to those for men. The women were only allowed to play two 30-minute halves. They are not allowed to wear studded shoes because of the high risk of injury. And their ball is a little smaller than the men's balls. Some of the arguments against women's football from the 1950s still resonate here.

Even before the DFB lifts the ban, Gelsenkirchen clubs set up women's teams. VfL Resser Mark 08 opens a women's team around 1969. On 6 September 1970, two women's teams play at the Glückauf stadium for the first time. The women's team from Spielvereinigung Resser-Mark in Gelsenkirchen faced a team from Vester Recklinghausen. The match is the prelude to the Bundesliga match between Schalke and Hertha BSC Berlin. In contrast to the men, the women are enthusiastic that afternoon. A year later, Eintracht Erle also founds its own women's team in 1928. When the DFB organises the first German Football Championship for women in 1974, the Erle women make it all the way to the final. However, their opponents from TuS Wörrstadt dominate the final in Mainz. In front of 4,000 spectators, they concede four goals to their rivals from Gelsenkirchen. Despite the defeat, the ladies from Eintracht Erle made a name for themselves. Their success does not go unnoticed at the FC Schalke 04 office either...

Schalke's president Günter Siebert likes the idea of a women's team in royal blue competing for the German championship. However, there is not enough time to build up a team. So Siebert makes Eintracht Erle an offer: Schalke takes over both women's teams, in return for which the Schalke men play a friendly match against Eintracht. The spectator revenue remains in Erle. Eintracht accepts: The club is short of cash. A few weeks later, female players are playing in the district league for their new club in royal blue jerseys. Unlike the men, they cannot make a living from playing alone. They are nurses by profession, work at the supermarket checkout or work for the city council. But football is their passion, even if some people smile at them: every weekend they lace up their boots and pull on the royal blue jersey against all odds. But then the 1980s began and the Schalke men started to stumble on the pitch. Money becomes scarcer. In 1987, Günter Siebert disbanded the women's section. It was 33 years before a women's team wore the Schalke jersey again.

Sources: FC Schalke 04, Institut für Stadtgeschichte Gelsenkirchen, Montanhistorisches Dokumentationszentrum (montan.dok) beim Deutschen Bergbau-Museum Bochum