The lock keeper squints his eyes. Something big is floating in the Rhine-Herne Canal. But he can't see what it is. It's just before six on this Thursday morning of 28 August 1930. Schalke doesn't sleep, Schalke never sleeps. Down below, the early shift is already at work again. The mates from the night shift are still trying to find their way to bed. And yet the lock keeper feels very alone right now. A person floats lifelessly down the canal in front of him. Despite the twilight, he can clearly make out the arms and legs. He runs to the bank and calls over. No response. Shortly before the bridge on Sutumerstrasse, the body washes up. Only now does he realise that the person is a man. The guard grabs him and heaves him ashore. But this is even worse. He shakes the man by the shoulders. He prays that he will open his eyes. The week had already started so badly. The West German Football Association had suspended the entire FC Schalke 04 first team at the beginning of the week. Even the biggest stars of Schalke's top flight were not spared.

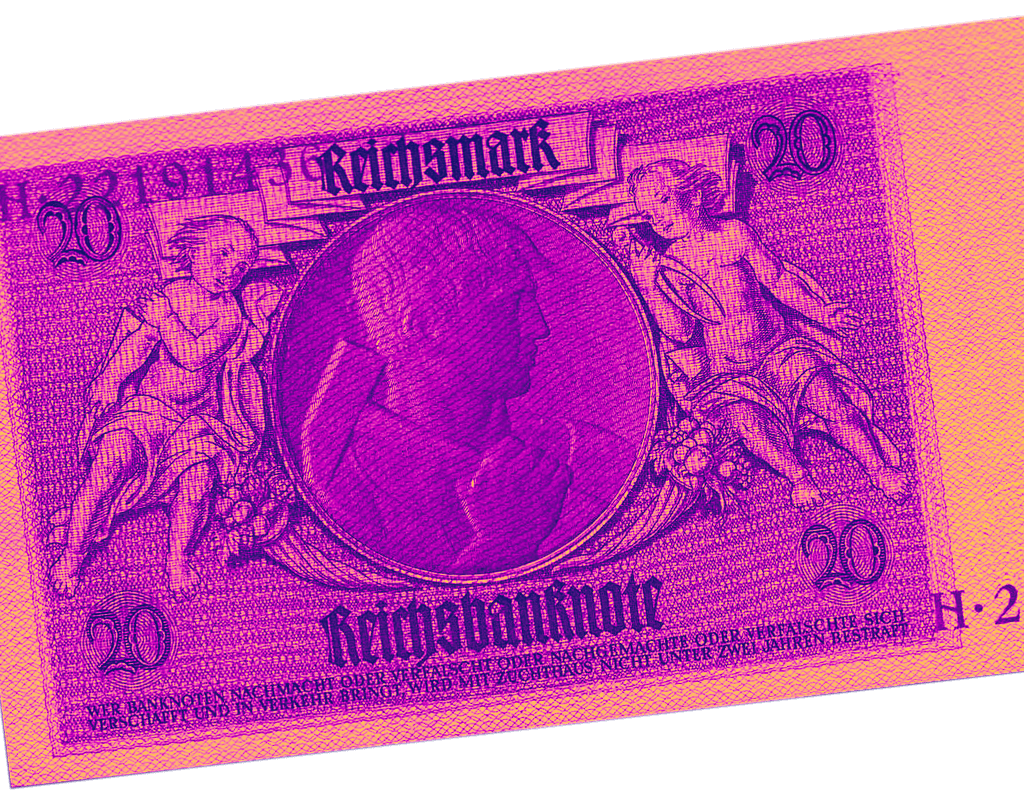

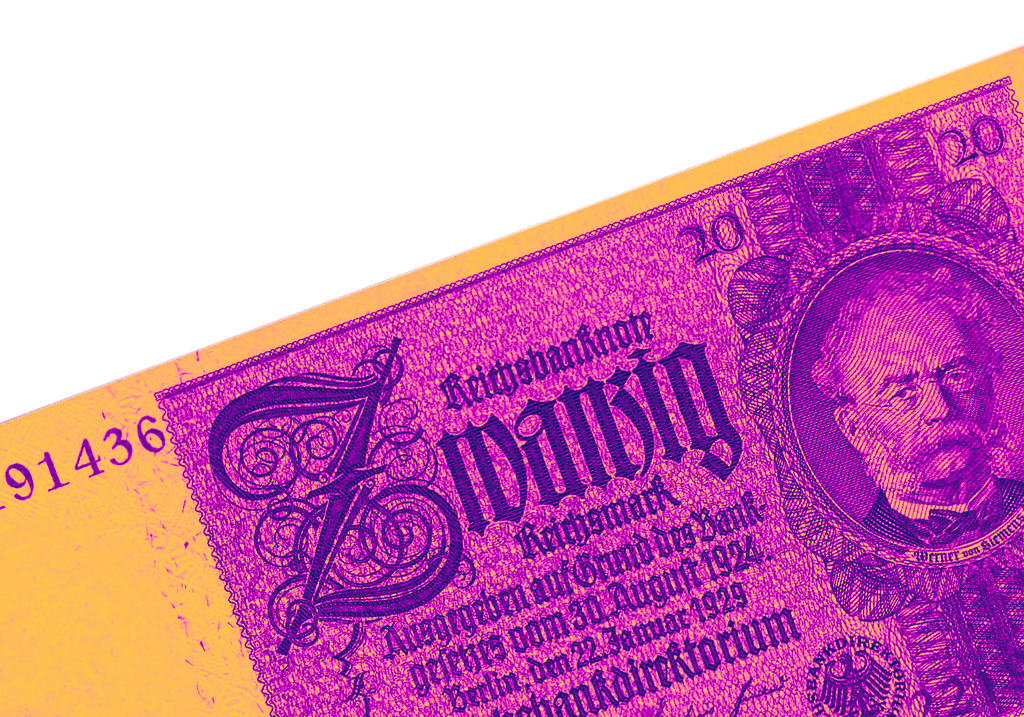

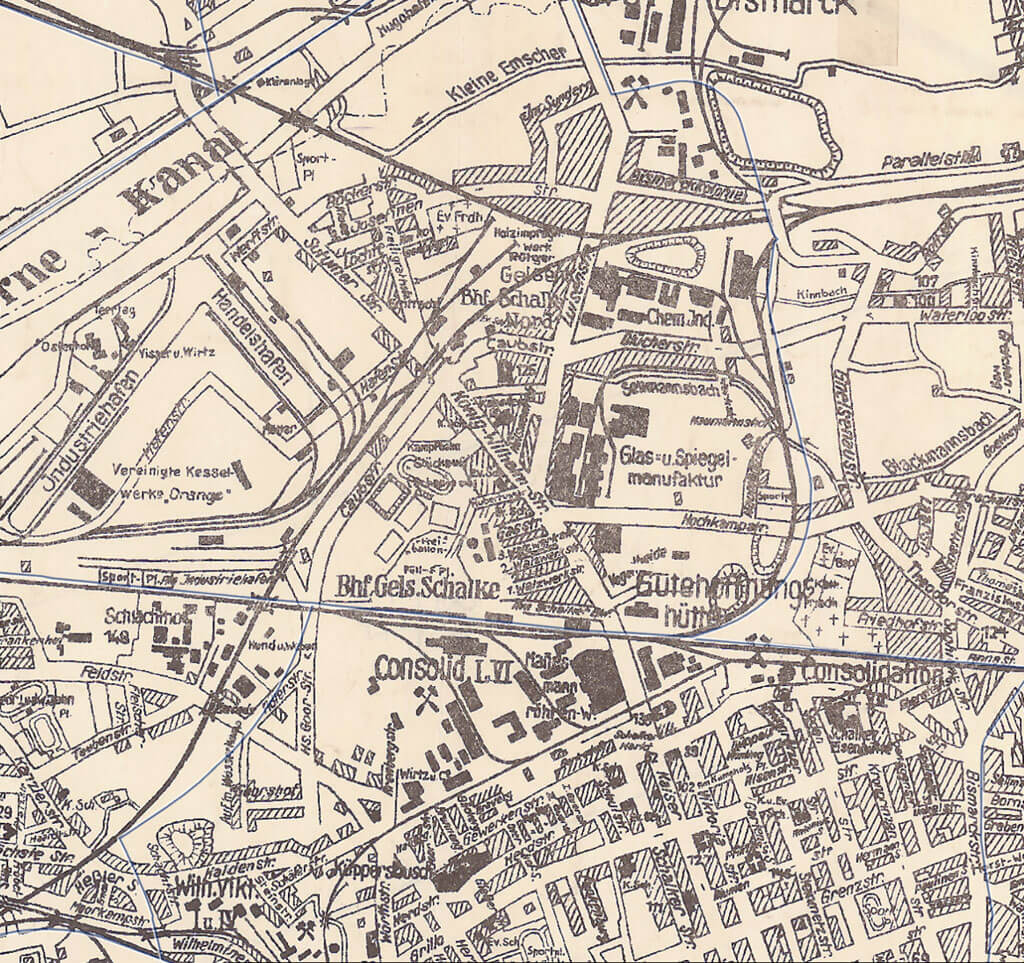

The weeks and months leading up to this Thursday have frayed the nerves of everyone at Schalke. The West German Football Association had brought charges against FC Schalke.The club was said to have secretly paid the team a lot of money after matches.10 marks per player.Officially, only 5 marks are allowed. This is because only amateurs are allowed to take part in competitions in Germany. Schalke is accused of sending professional players onto the pitch. The people at Schalke are stunned. It is an open secret that the other clubs also pay their players more than is permitted. And the money that football generates is not enough to live on. After all, the lads all work. Ernst Kuzorra and Fritz Szepan, for example, in their tobacco shops, Walter Badorek as a miner at the Consolidation colliery and Valentin Przybylski as a warehouse clerk. The Schalke players have an idea of what it's all about: the "Proleten- und Polackenclub", which has been stirring up the competitions for a few years now, is to be taken out of circulation.

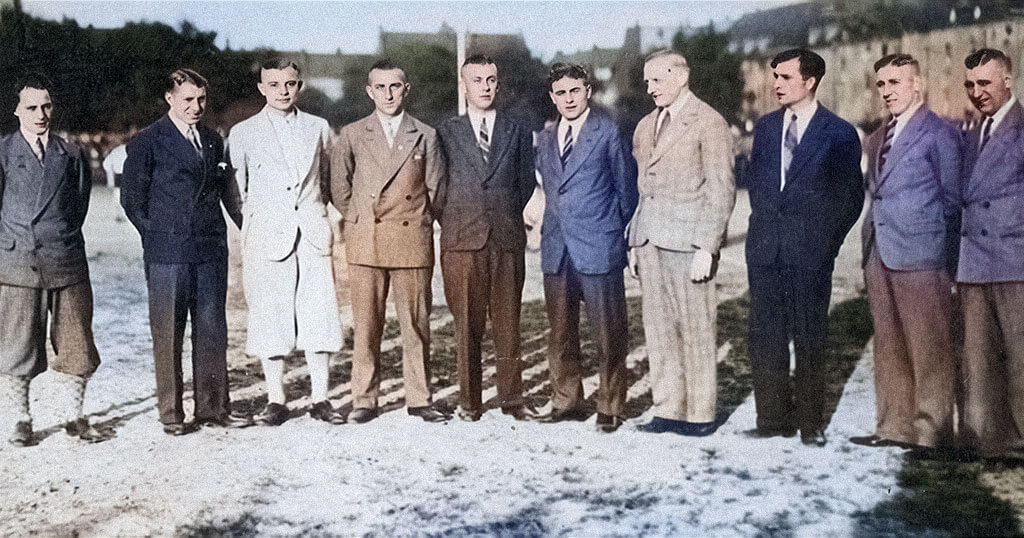

After several hearings of Schalke players and officials, the West German Football Association announced its verdict on Monday, 25 August 1930: the entire first team and eight officials of FC Schalke-Gelsenkirchen 04 were banned for life. The reigning West German champions are brought to an abrupt halt. People are horrified by the severity of the judgement. Why Schalke? Why is the association only relentless with the club from the industrial district? The bourgeois patent shoe clubs pay their players at least as much money. The mood on the Schalke market is at rock bottom. The club is scraping together a makeshift team for the coming season. The players from the Schalker Kreisel are no longer allowed to play. After chasing success after success in recent years and playing their opponents into the ground with finesse, they are now condemned to watch from the sidelines. Dark clouds gather over Schalke, and the lock keeper pulls a dead man out of the canal three days after the judgement.

The lock keeper finds a wallet by the body. With trembling hands, he takes out various papers and letters. Most of them are addressed or made out to one name: Fritz Szepan. The guard's thoughts are racing. Has he just pulled the Schalke striker lifeless out of the water? He runs up the embankment to the police station on Sutumerstrasse. He has to get help. One of the officers recognises the dead man. It's not Szepan. The man lying on the grass in front of them is Wilhelm Nier. He is the chairman of the FC Schalke 04 finance committee, one of the officials banned by the WSV. When the fire brigade arrives to pick up Wilhelm Nier, there are only a few people on site. Nevertheless, the news spreads like wildfire: they have pulled Willi out of the canal, less than three days after the judgement. That can't be a coincidence. The next day, Willi Nier's death is in all the newspapers. The man who had overseen FC Schalke's meteoric rise as finance chairman is no more.

Nier recognised early on how important it was for the club to have its own stadium. As early as 1926, Schalke 04 was known beyond the borders of Gelsenkirchen for its beautiful game. Every weekend, people from all over the Ruhr region flock to Schalke's home matches. Up to 40,000 fans turn up to watch high-calibre opponents. Too many for the pitch on Grenzstraße. The squires often have to switch to larger pitches in the neighbourhood. But Nier doesn't just see the lack of space: he also sees the entrance fees that the club could earn. Together with Fritz Unkel, he convinces the members in 1927: Schalke needs its own stadium. A stadium like no other in the Ruhr region. However, the construction would cost 200,000 marks, a huge sum. It is only thanks to Willi Nier and his financial skills that the stadium can be built. In 1928, Schalke inaugurate their Glückauf stadium, one of the largest club-owned sports facilities in Europe. It could hold 34,000 spectators. And it is located right next to Schalke-Nord railway station.

And now one of the fathers of Kampfbahn Glückauf lies dead on the banks of the canal. The police and reporters from the local press quickly set about reconstructing Willi Nier's last day. He initially spends the evening of Wednesday 27 August at Haus Thiemeyer on Schalker Markt. Nier appears dejected to the guests present. The otherwise cheerful man only gives terse answers. Finally, he leaves the Thiemeyer house. He visits the second chairman of the club for a chat. He is then seen talking to his wife at the Schalker Markt. He then walks towards Oststraße, presumably to buy cigars on the corner. It is perhaps 7.30 pm. Nier's trail then disappears between the residential buildings and the industrial plants. It is not known how he reaches the canal and where he makes his final decision. Perhaps he walked up Kaiser-Wilhelm-Straße one last time to see "his" Glückauf stadium for the last time.

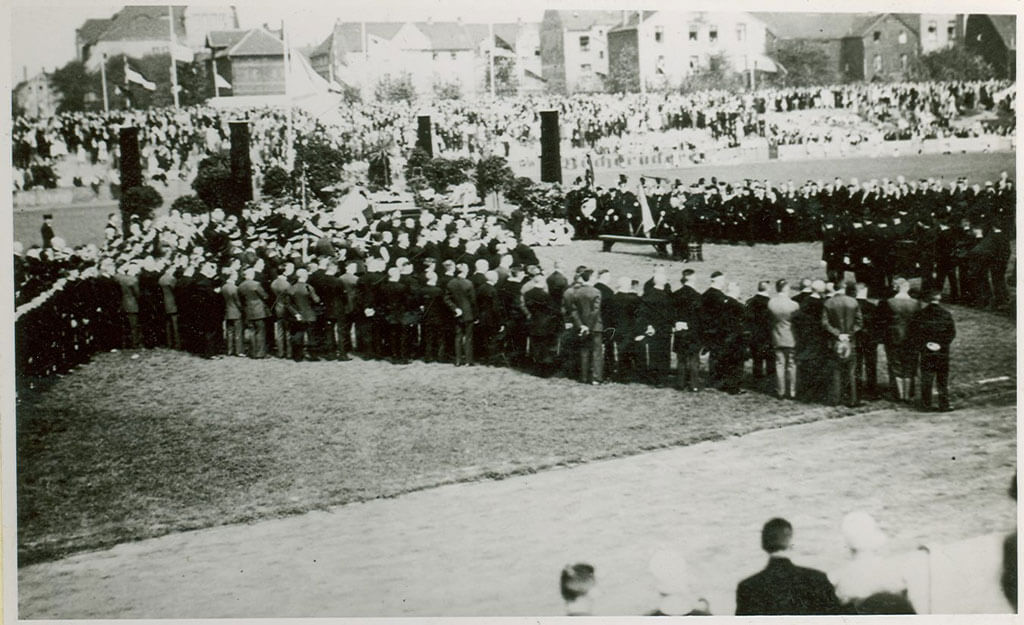

On Thursday morning, the Schalke family gathers at Haus Thiemeyer, their headquarters. The horror is written all over their faces. Members, officials and players sit at the tables and stare at each other. Willi is no longer among them. He, who has always stood up for the club. And yet things were only just about to really get going. The new stadium and the first West German championship should only be the beginning. This year will see the start of the construction of a new reception hall for Schalke-Nord station. This will make it even easier for Schalke fans travelling from outside the city to attend home matches at the Schalke Kreisel. But nothing is certain any more. Can the reserves even stay in the league? Will the club ever again find the exceptional talents that Kuzorra and Szepan were? And if the Schalker Kreisel is no more, will this huge stadium even be needed? The future looks bleak. But now they have to take care of Willi. He is to be given a big funeral service in his stadium. At the club's expense.

Willi Nier will be laid to rest in Rosenhügel cemetery on Sunday, 31 August.However, the coming weeks and months remain turbulent. Word quickly spread in Europe that the players from the Schalke squad were without a club. Ernst Kuzorra and Fritz Szepan both receive an offer from Vienna. It is not illegal to play professional football in Austria. Each of them is to receive 1,000 marks per month at Admira Vienna. They have to feed their families somehow. They sign. Everything seems to be crumbling apart. But the West German Football Association is also under pressure. The public criticises the ruling ever more loudly. When it became clear that the association would soon lift the bans, Kuzorra and Szepan cancelled their contracts with Vienna. If they can choose, they play for Schalke. The world looks different again in the summer. The reserve team has kept its place in the league and the association has lifted the bans again. On 1 June 1931, the Schalker Kreisel plays for the first time again at the Glückauf stadium with its original line-up. The players play a friendly match against Fortuna Düsseldorf.70,000 people flock to the Glückauf stadium on this Monday. But it is only designed for 34,000.

The scandal surrounding the payment of expenses is neither the only nor the last scandal involving FC Schalke 04. In 1993, for example, a financial scandal was brewing at Schalke:The then president Günter Eichberg amassed a huge mountain of debt. He tried to conceal just how big the mountain actually was. After Eichberg's departure, the club was able to avert the threat of licence revocation and forced relegation. In the 1970s, money payments were also at stake. In 1971, the Royal Blues surprisingly lose at home to relegation candidates Arminia Bielefeld on match day 28 at the Glückauf stadium. A DFB sports tribunal later determined that the defeat had been bought. Every Schalke player on the pitch received 2,300 marks in cash after the final whistle. Half the league is involved in the infamous Bundesliga scandal. The DFB penalised around 50 players, including 13 Schalke players. At that time, clubs were allowed to pay their players a maximum of 1,200 marks per month. The regulations on capping salaries were not lifted until 1972.

Image sources: FC Schalke 04, Institute for City History Gelsenkirchen