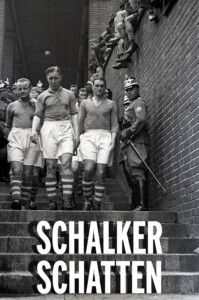

Match day in the Arena. Tens of thousands of people in blue and white flood the paths around the stadium. They stream from the car parks and train stations towards the temple of glass and concrete. Their path leads them along streets dedicated to the club's most important players. The street names commemorate the people who made the club what it is today. Stan Libuda, Ernst Kalwitzki and Ernst Kuzorra can be found here. One name, however, is missing: Fritz Szepan. But the reason for this is not on the pitch. Szepan is undoubtedly one of the greatest footballers ever to wear the royal blue jersey. He was the pacemaker and director of Schalke's top line and also contributed to the S04 legend. The reason for this lies off the pitch: Fritz Szepan was more closely involved with National Socialism during the Third Reich than the other players on the Schalker Kreisel.

When the National Socialist Workers' Party (NSDAP) came to power under Adolf Hitler in 1933, FC Schalke 04 adapted to the new conditions. As part of this adaptation, for example, Jewish members were excluded from the club. Schalke was no different from most other clubs. What set the Royal Blues apart from the other clubs was their sporting superiority. Between 1934 and 1942, they won the German championship six times. Schalke's most successful years (so far) were therefore during the Nazi era. This is why some people still think today that Schalke must have been a Nazi club whose successes were bought by its closeness to the regime. Various studies have since refuted this claim. There were no ardent supporters of National Socialism among the Knappen. And their sporting success was due to their superior style of play, which they had cultivated and improved since the mid-1920s. The Schalke team's sporting breakthrough had already been heralded in the years before the takeover.